R. Buckminster Fuller’s 22 Self Disciplines For Life & Business Success

From dramatic business failure and on the brink of suicide, R. Buckminster Fuller had an epiphany and became one of the greatest minds of…

Richard Buckminster Fuller. Image courtesy of Buckminster Fuller Institute

From dramatic business failure and on the brink of suicide, Richard Buckminster Fuller had an epiphany and became one of the greatest minds of the 20th Century. Here’s how he did it.

In 1927, Buckminster Fuller found himself in financial ruin and personal turmoil. Five years earlier, his first child, Alexandra, had died aged four from spinal meningitis. Now his construction business had failed, leaving him ruined and family investors with nothing. Fuller was reclusive, depressed and drinking heavily. As he considered drowning himself in Lake Michigan, he had an epiphany and began to redesign his life. He assigned himself as a human guinea pig in a lifelong experiment and documented progress in what he called the “Cronofile”. He subsequently established 22 self disciplines that were to become the foundation stone of a globally successful career. By his life’s end, Buckminster Fuller had become a renowned inventor, design architect, and globally recognised thought leader in sustainable technology. These are the core principles that guided his life and career.

I am not precisely sure how I came first to read the work of R. Buckminster Fuller. I suspect it was through an advocate of his, philosopher and author Alan Watts perhaps. Regardless, certain people come our way who make an indelible impact on our thinking and Buckminster Fuller, for me, has been one of those people.

Fuller believed in a Universe that was generative and self-supporting, self-sustaining and built with the inherent ability to provide substantially for all life forms it contained. Within the fabric and structure of this self-supporting universe, he postulated a self-managing universal accounting system that ensured success and abundance for all life on earth and beyond.

Opposingly, he highlighted the folly of what he called the selfish and fearfully contrived “wealth games” that humanity plays under a misinformed survival-of-the-fittest ideology. In the playing of these wealth games, he held that humanity would ultimately destroy itself. However, in that, he offered a solution.

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality.

To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete”

Fuller’s Global Vision

Fuller held that if an individual free from the constraints of dogma and ideology were to attempt via all resources available to him/her, through non-self-centred motivation, to create real solutions to humanity’s problems, then in our inevitable evolution towards better, humanity would adopt these solutions. His self-made commitments reflected this core belief and directed his life’s work towards global solutions and the advancement of all life on the planet. Something to which, he suggests, no nation, private enterprise, religion, or other multi-peopled, bias-fostering combination of individuals has ever managed to accomplish.

Buckminster Fuller’s ideals were honourable. However, given the current momentum of the world of people, I believe we will eventually destroy ourselves, despite the efforts of people like Buckminster Fuller. In that self-destruction, we will exercise the very self-sustaining forces of the Universe highlighted by Fuller because the survival of the larger organism will always supersede that of any individual species. It can never be any other way. The whole will always seek out homeostasis — equilibrium at the expense of any single entity or species.

I want to be wrong, but given our current stage of evolution and our openness to propaganda and mongering of fear, I can’t but expect it. The vast majority of human beings only know self through associations with the larger group — the collective self. And it is through this group identity that our thoughts and beliefs are sculpted. Our thoughts are automatic and predictable. We crave more things, higher social status and acceptance even down to our micro-social interactions. Paradoxically, it is in this attempt to find validation through the relationship with others, that we become incapable of seeing our true selves and subsequently, the impact of our actions on our collective existence.

Even so, Buckminster Fuller pursued an honourable line and proved the validity of his position time and time again. Although in the early days, things may not always have good for him and his family, he held to his convictions nonetheless and became a marker for individual human achievement.

Who Was R. Buckminster Fuller?

Richard Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller was a highly regarded and respected 20th-century inventor and visionary, but his beginnings would not have suggested the level of success he achieved. He was born in Milton, Massachusetts on July 12, 1895, to Richard Buckminster Fuller Snr and Caroline Wolcott Andrews. In 1913 Fuller entered Harvard University but shortly afterwards was dismissed from for excessive socialising and missing exams. Subsequently, he spent time working in a sawmill, and after unsuccessfully attempting to renew his Harvard education, he later joined the US Navy where he became an officer.

Leaving the Navy after WW1, Fuller entered the business world. He joined his father-in-law in the construction industry opening four factories creating building components. But the business ultimately failed, leaving Fuller penniless and disgraced, losing investments made by family and friends in the process. Such was the financial loss and the loss to his sense of self; he became profoundly depressed and contemplated suicide. Spending nearly two years as a recluse, in deep contemplation about the nature of his relationship to the world, he realised he couldn’t end his own life. Instead, he decided to discover how he could make the most valuable contribution to the whole of humanity through the systematic design and application of technology.

“I live on Earth at present, and I don’t know what I am. I know that I am not a category. I am not a thing — a noun. I seem to be a verb, an evolutionary process — an integral function of the universe” — R. Buckminster Fuller

Parochial & Narrowly Focused

Buckminster Fuller realised that society was preoccupied with individual, local and national focused issues. In the pursuit of self-serving interests, politicians, business leaders and those of influence couldn’t give credence to global problems with any real conviction. The political vision was too narrow, and collective thinking was too short term.

When we see our lives as finite as opposed to ever-lasting through subsequent generations, when we cannot see beyond the scope of our self-interest, it becomes impossible to serve humanity as a whole. Resources seem finite in this finite state of mind, and therefore, we justify all kinds of outrageous acts in pursuit of growth and survival.

To Fuller, it seemed clear that only an individual operating on their own economic and philosophical initiative could reveal the solutions required to humanity’s global problems. And so, he decided to dedicate his life to creating a world that works for all human beings equally rather than the gilded 1%. He became a practical philosopher demonstrating his universal concepts through inventions, which he termed “artifacts.”

Fuller did not limit himself to one field but worked as a “comprehensive anticipatory design scientist” attempting to solve global problems associated with education, energy, environmental destruction, and poverty.

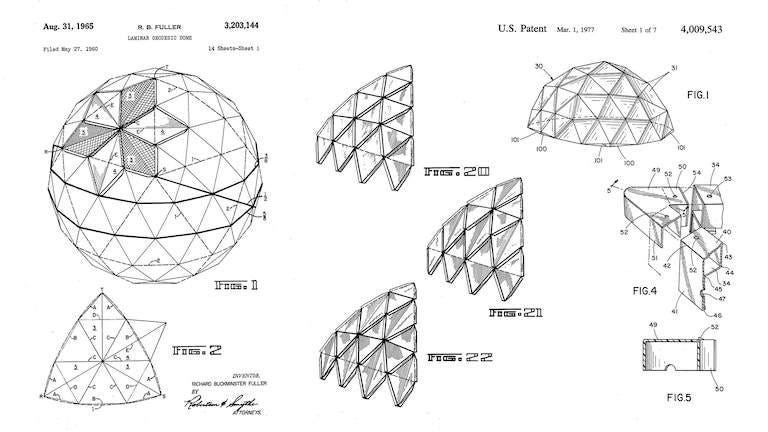

Throughout his life, Fuller held 28 patents, wrote 28 books and was in receipt of 47 honorary degrees. The Geodesic Dome has been produced over 300,000 times worldwide, is Fuller’s most well-known artifact and greatest monetary claim to fame. The geodesic dome — the hemispherical structure (lattice-shell) based on a geodesic polyhedron.

1965 Patent for the Geodesic Dome

The 22 Self Disciplines of R. Buckminster Fuller

Upon reading of Buckminster Fuller’s business failure, his story developed greater significance for me. I could relate to the time he spent in solitude, attempting to figure himself out, to understand his place in the world. I felt further vindicated and redeemed for the experience of my earlier business failures.

It’s a strange feeling when we find others out there on the ragged rim of life who have gone through things we have. There is camaraderie, a kinship and an understanding — a sense that we are cut from the same cloth.

We have to be careful, however, not to congratulate each other too much, or indeed wallow in our defeat. Reading Critical Path, Fuller’s final published book, there is certainly not the sense of his wallowing in that first defeat. On the contrary, after his emergence from the cocoon of his 2-year self-imposed solitude, it seems he had the seed of something diametrically opposite to that first failure. He had something that would subsequently grow exponentially bigger as he predicted.

“Everything you’ve learned in school as “obvious” becomes less and less obvious as you begin to study the universe. For example, there are no solids in the universe. There’s not even a suggestion of a solid. There are no absolute continuums. There are no surfaces. There are no straight lines.”

Other things Fuller wrote about, such as ‘spontaneously engendered support’ resonated with me also. Fuller believed if he were working for the benefit of all humanity, then the necessary support required would appear when needed.

At his absolute low and contemplating suicide, with a young family, penniless, and as he put it; a throwaway in the business world, he made a series of resolutions. These self-disciplines, coupled with influences from his earlier life, would prove to be the solid ground upon which he was to build his life and work success.

In Chapter 4 of Critical Path, Fuller outlines his 22 self-disciplines, although the first six or so don’t seem like self-disciplines to me. Instead, they seem like false ideas planted in his young head, which he recognised and needed to overcome. They subsequently led to the establishment of self-disciplines that would guide his career. Regardless, he had a unique style of writing so I will be faithful as possible to the book and include them as he has done.

#1: Never Mind What You Think.

Fuller’s mother said it, his teachers said it, every grownup authority he knew told him the same thing; you can’t think for yourself. Individual thought wasn’t something one could engage in without the supervision of those who knew better, and children were certainly not to be trusted to think for themselves. As he put it; thinking was considered to be an utterly unreliable process when spontaneously attempted by youth.

So he did what he was told, for a while.

#2: Love Thy Neighbour

Fuller’s parents raised him in the Unitarian church where his grandfather was a preacher. His grandmother taught him to love thy neighbour as thyself, do unto others as you would they do unto you. Although it seems he left aside the dogmatic ideology of his religion in favour of experience-based scientific facts, a concept of God appeared to stay with Fuller. Albeit somewhat different from traditional religionist thinking.

#3: Life Is Hard

As he grew older, his uncles and other males of influence in his family began to preach opposite of his grandmother’s Christian principle. They reinforced the idea that life was hard and that although grandmother’s golden rule was nice, it wasn’t practical. His uncles’ life-is-hard belief encouraged young Richard to accept that if he were to provide for himself and a family, then he would have to deprive other people of a comfortable life. Survival of the fittest took over.

#4: Follow The Rules

The rules seemed to be written by others, and the young Fuller began to accept that he needed to follow them. He ignored his own thinking and trained himself, albeit on autopilot, to follow the rules of the game of life as given to him by his family.

#5: Learn To Cope

With this ideology taking firm hold, it seemed that he couldn’t bring himself to win over and sacrifice others to his own ends. After leaving the Navy and finding himself in the competition based business world, he turned out, as he called it, “a spontaneous failure”. He says; “I was sure I could cope with hardship better than the other guy, so I would yield”. It seems he struggled to operate in this dog eat dog world of business.

“Everyone is born a genius, but the process of living de-geniuses them.”

#6: Form An Integrated Self

In 1907 it was poet Robert Burns who inspired Fuller with his 1786 poem, To A Louse, and the line;

O wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

Fuller opted to integrate the self he saw as him, with the self others saw and to deal as objectively as possible, the world around him.

With this conviction, he began recording his life in what he called “The Chronofile”. This record consisted of every written record of his engagements both good and bad, with the world and others in it.

Today, Fuller’s Chronofile is housed at Stanford University and contains an entire account of his life and work from that fateful day in 1907.

Self Discipline #7: See oneself as an experiment

After his return from the edge of despair, Fuller sought to set himself as the subject in a life long experiment with himself as the guinea pig.

The experiment was designed to uncover what, if anything, a healthy young male of average size, experience and capability, with dependants, no capital or access to credit, could do to alter the fortunes of humanity effectively.

A brave move, something that goes against popular convention and advice one would be expected to receive given Fuller’s financial condition at this time.

Later in the book, he admits that things did not always go to plan.

Sometimes he had to take meagre paying jobs to meet his bills, but eventually, he would return to his base commitment and continue his experiment.

#8: Serve All Humanity

Perhaps an idealistic and naive position to take, but Fuller decided to dedicate himself to provide solutions to all humanity equally.

He resigned to serve the interests through his work, of all human beings as opposed to traditional personal and business motivations which aim to self serve first and foremost.

He insists that his decision was not taken recklessly or on a naively altruistic basis. But to think instead based on evidence contained in his Chronofile, which demonstrated that when he was motivated to serve others first, then he would be adequately compensated.

#9: Think For Yourself

Buckminster Fuller sought to think for himself, confining it to information gained directly from his personal experience.

He sought to move from a centred place of innate motivational integrity rather than trying to accommodate the opinions, values and theories of other people.

A difficult task, given that we are always open to influence from others, subtly through our belief about their authority and knowledge.

Perhaps Fuller was more aware of his need to question his personal assumptions and assertions of others no matter their background.

Self Discipline #10: Never at the cost of others

He sought to pursue and develop his ideas for the benefit of everybody and at the expense or loss to nobody else.

The predominant mode of thought in business and industry is that there will be necessary casualties in the pursuit of this new idea of ours. The environment may be affected. Other human beings may be affected, even killed in the process, but that’s ok because our pursuit is in the better interest of humanity as a whole.

In our self-exalted, self-righteous, do-gooder state of mind, we make it ok.

Fuller was as integrated a human being as I have found thus far in my 45 years. He saw himself as part of, and working with, the process of life and not an adversary of it.

“Every atom and electron is an essential part of the eternally regenerative — ergo, totally inexhaustible, but always ebbing and flowing — pulsative Universe.”

Self Discipline #11: Emancipate humanity from unfavourable conditions

Buckminster Fuller sought to reduce his technological ideas to physically working models. These model were designed to counter existing unfavourable conditions, predominant customs and societal afflictions so much so that he could emancipate human beings from their adverse circumstances.

These new inventions would provide society with technological advances and reforms that previously proved impossible by social change. Fuller sought to reform the environment through technology, not human beings.

Self Discipline #12: Never promote oneself

Fuller sought never to promote or sell himself or pay anyone else to do so. A remarkable position to take, the full extent of which I am not fully aware. However, this self-discipline is very interesting to me, for how does someone spread the word about their product or service if we were not to promote it?

This question needs further investigation on my part.

He went on to say that he would never hire agents or personnel who would solicit the support of any kind for his work. He held that humanity would adopt his new systems and inventions when there became a survival need which would come about by evolutionary means.

Self Discipline #13: Develop patience

Fuller assumed that nature and the universe as a whole, had its own unique gestation period, not only for biological elements but for technological inventions also. As such, he knew he didn’t need to force compliance from anyone or anything. He knew that time would ripen his technology and people’s attitudes towards it.

To me, it seems that Fuller was aware of the timeless nature of existence, that all there existed was an eternal moment where life evolved. We have since uncovered through research, that time is subjective, not objective. It seems to me Fuller knew this.

“I just invent. Then I wait until man comes around to needing what I’ve invented.”

Self Discipline #14: Accept the spontaneity of acceptance

Connected to self-discipline #13, Fuller believed that humanity would inevitably adopt the devices and systems he created and so he sought to develop his artifacts with the necessary time margin anticipated.

In other words, he believed that there was no need to rush his work or push or pressure for his ideas to be adopted. He assumed that nature would evaluate his work as he progressed, providing he worked with nature’s fundamental principles.

“If you want to teach people a new way of thinking, don’t bother trying to teach them. Instead, give them a tool, the use of which will lead to new ways of thinking.”

Self Discipline #15: Learn most from mistakes

He sought to learn the most from his mistakes but never to ponder in worry or procrastination. Fuller recognised that when he worried, he felt sad. But when he always sought to learn and progress, he felt happy. In this, Fuller adopted a simplistic and practical way forward. He, therefore, never allowed his emotional state to disrupt his progress.

“Mistakes are great, the more I make the smarter I get.”

Self Discipline #16: Waste no time in worry

As mentioned above, Fuller sought not to ponder failure and instead, as he put it;

“I sought to…increase time invested in the discovery of technological effectiveness.”

Self Discipline #17: Document progress in the official records

Fuller had no university degree, so to document his progress in the public records, he sought patents for all his inventions. Some of these expired worthless, while some provided an income. But as he stresses in Critical Path, his motive was not to make money from the patents and didn’t recommend going the patent route due to the high cost.

Self Discipline #18: Comprehend the principles of regenerative Universe

Above all, Fuller sought to understand and work with, the fundamental principles of what he termed; “eternally regenerative Universe” and subsequently implement these principles in the design and manufacture of his artifacts.

Self Discipline #19: Educate oneself comprehensively

The breadth and depth of scientific knowledge is vast, but that didn’t stop Fuller from undertaking the comprehensive education of himself. He sought to digest comprehensively the inventory of human understanding of all chemical compounds, weights, performance characteristics, the effect of the interalloyability, and so on.

It didn’t stop there.

Fuller undertook to consume all the data he could relate to economics, global demographics, energy production capabilities, logistics and vital statistics yet amassed by human beings.

A tall order.

Self Discipline #20: Operate on a do-it-yourself basis

He sought only to operate as a business of one — a remarkable undertaking. I’m sure you’ll agree. If he couldn’t do it by his own ingenuity, then it wouldn’t be done.

Self Discipline #21: Provide advantage to new life

Inspired by the healthy birth of his second child, Allegra in 1927, Fuller says; I oriented what I called my “comprehensive, anticipatory design science strategies” to primarily advantage new life to born within the environment-controlling devices I was designing and developing”.

He realised the problems humanity encountered would take fifty years to solve and organised groups such as governments and corporations were incapable of providing the solutions. For his daughter and all-new human life to live in a better world, he would have to get his hands dirty.

Self Discipline #22: The role of God

Given Fuller’s religious upbringing, it seems from reading the work that he needed to somehow integrate the God of his religion into the set of beliefs he built based on scientific knowledge and personal experience. For many God does not belong in science; however, I believe that a God can be reconcilable with science and the fundamental laws of the universe. Buckminster Fuller understood the same.

In his final note on his self-disciplines, he refers to this final one as perhaps containing the most significant weight and influence. As such I think it best to offer Fuller in his own words.

At the outset of my resolve not only to do my own thinking but to keep that thinking concerned only with directly experienced evidence, I resolved to abandon completely all that I ever had been taught to believe. Experience had demonstrated to me that most people had an authority-trusting sense that persuaded them to believingly accept the dogma and legends of one religious group or another and to join that group’s formalised worship of God. I asked myself whether I had any direct experiences in life that made me have to assume a greater intellect than that of humans to be operative in Universe…I said to myself, I am overwhelmed by the only experientially discovered evidence of an a priori eternal, omnicomprehensive, infinitely and exquisitely concerned, intellectual integrity that we may call God, though knowing that in whatever way we humans refer to this integrity, it will always be an inadequate expression of its cosmic omniscience and omnipotence.

Buckminster Fuller, Critical Path

Applying Buckminster Fuller’s Self Disciplines

Play To Your Highest Level

It appears that in the depth of his depression and upon the imminent destruction of self, there spontaneously arose in Fuller’s consciousness a greater meaning and purpose for life. In this, he found a reason to live and play the game at an intrinsically motivated, and consequently, to the highest level.

This is our only responsibility. Limits are necessary but merely temporary boundaries we must discover how to overcome. I believe if we follow our inspiration and curiosity, those boundaries become ever-increasing outer circles of the self.

Follow Your Own Path

Buckminster Fuller’s achievements were remarkable, and I have significant admiration for him. But there is not an imperative for us to attempt to emulate his achievements or that of any other successful person. To try to do so is naive because each of us is unique.

We are meant to be who we will be, and although we can admire the achievements of great people, we must accept that they are as unique as we are. We must follow our own path.

Place Personal Integrity Above All Other Values

Extrinsic motivation such as the pursuit of status, cars, planes, attractive side-kicks, and money in the bank are materially rewarding consequences of focused daily work. They can not sustain us in their own right. There has to be something more to life than stuff.

Fuller says of integrity;

“So it is this matter of the integrity of the individual, the courage, the courage to go along with the truth as you personally really see it — or are you going to be swayed by the crowd? Are you going to be scared about your job, or whatever it may be? Integrity of the individual is what we’re being judged for and if we are not passing that examination, we don’t really have the guts.”

We each have a responsibility to only ourselves, to be true to whatever it is that calls us. Buckminster Fuller was the perfect example of this for me.

Realise Yourself As One With Universe

The exploration of quantum level realities has taught us that there truly is no separation between people and things. We are, quite literally, made of the same stuff and there are no boundaries of that stuff, only fluctuations and patterns.

It is the limit of our sensory equipment, of perception, that brings into awareness the boundaries of individualities. I believe it is the next step in the development of humanity that we consciously, as we move about our day, realise the literal oneness of ourselves and the environment.

There is no separation, and Buckminster Fuller considered this in all his life’s work.

“There are no solids. There are no things. There are only interfering and non-interfering patterns, operative in pure principle, and principles are eternal.” — Buckminster Fuller

Thanks for taking the time to read my stuff. If you enjoy Sunday Letters, consider supporting my work. I’m on Twitter if you’d like to follow me there. Oh, and there’s the Sunday Letters Podcast.

ARTICLE REFERENCES

“Self-Disciplines of Buckminster Fuller.” Critical Path, by Richard Buckminster Fuller, St. Martin’s Press, 1981, pp. 123–160.

Burns, R. (n.d.). To A Louse. Retrieved May 06, 2019, from http://www.robertburns.org/works/97.shtml

Fuller, R. B. (n.d.). R. Buckminster Fuller Collection. Retrieved May 06, 2019, from https://library.stanford.edu/collections/r-buckminster-fuller-collection

Bfi.org. (2019). The Buckminster Fuller Institute. [online] Available at: https://www.bfi.org [Accessed 6 May 2019]